I think that writing a good song or designing a nice chair is a skill you can learn.

The problem is that learning to write or design is not like memorizing the capitals of the 50 states. For me, that sort of rote learning is like gathering up a good collection of bottle caps and stashing them in a drawer.

Learning to design and write, on the other hand, is more like building a bottling machine when you’ve never even seen one before. You have to assemble lots of unfamiliar parts and get them working in concert.

One common piece of advice is to visit lots of other bottling plants to see how their machines work. In other words, listen to a lot of really good music to learn to write a song. Look at a lot of really beautiful pieces of furniture to learn to design your own pieces.

I give that piece of advice all the time. But it leaves out an important first step. You first need to learn to see and to listen. And learning to see or listen is damn hard.

That’s because when we look at a piece of furniture or listen to the radio, our brain simplifies the stimulus into a single object or sound, when it really is a combination of a bunch of complex shapes and sounds.

How do you force yourself to see? Here’s how I do it.

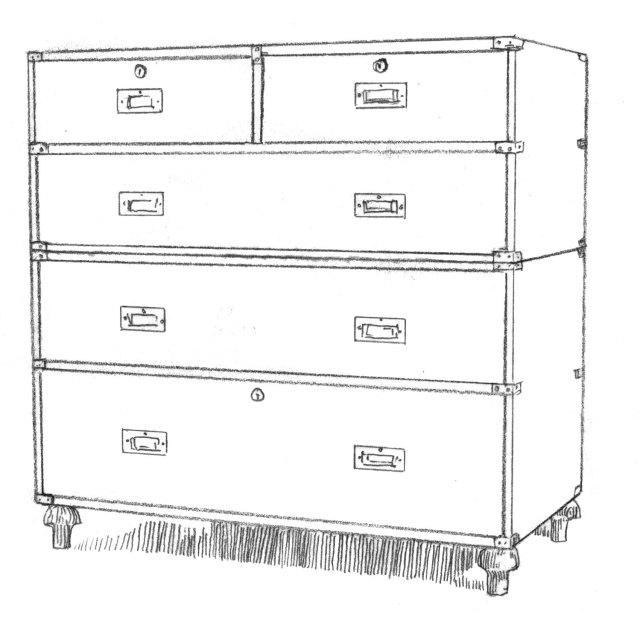

It came by accident when I was working on “Campaign Furniture.” Many of the drawings in that book are tracings that I made of photos I’d taken in years prior. As I traced each piece, I was forced to examine the shape of every turning, moulding and component. I had to draw both the major forms and all the minor details. In other words, it forced my brain to stop seeing the whole piece and focus on all the small elements.

As I traced more than 100 pieces, I began to see obvious patterns. The handles of campaign chests were spaced above the centerline of each drawer. The stacking chests had drawers that refused to graduate (Fibonacci is a fibber). Sometimes the pieces got away with awkward drawer arrangements that looked dang good.

I also noticed so many little details. The best chests used drawer blades that were hidden – a detail I missed until I started drawing them. And I got a great feel for the beads and tapered cylinders that made up the feet of the chests.

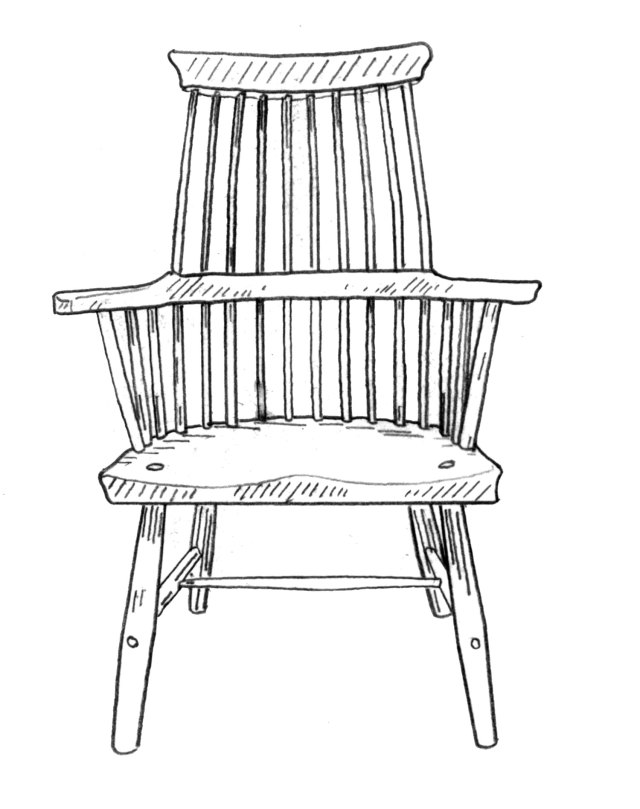

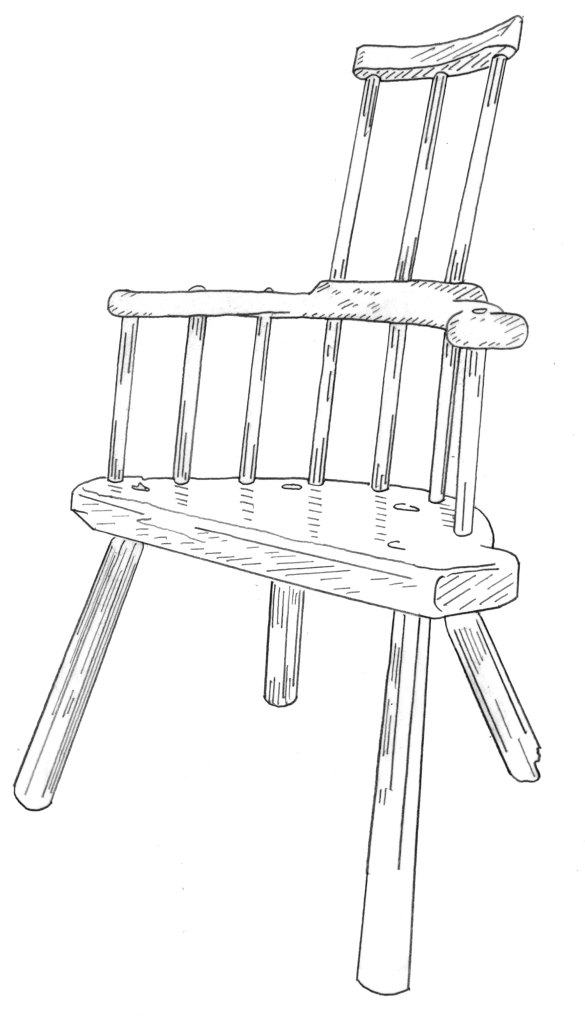

So when I decided to stop copying old stick chairs and strike out on my own, my first step was to buy a pad of tracing paper at the grocery store. I then opened the enormous folder on my laptop of chairs that I love, picked the 50 best and printed them out. Then I began tracing them.

To be honest, once I started tracing chairs, it was difficult to stop. My pencil forced me to see so many things I had glossed over before. Chair shapes that I thought were complex were reduced to the squares, circles, rectangles and arcs I learned at Robin Wood Elementary.

I saw – for the first time – how certain elements were grouped together. Many beginners think that a design element should be carried throughout the entire piece. Matchy-matchy – like Garanimals. That’s how we got the California Roundover style, the nadir of furniture during my lifetime.

Instead, I learned how circles and rectangles worked together with the occasional irregular curve to make something that looks right.

I know, this is a boring and arduous way to learn design. There’s no Zen koan. Instead, it is a gradual revealing of the structure behind our world – one pencil stroke at a time.

— Christopher Schwarz

P.S. And if you want to learn to write a good song (and to learn to listen), try this.